"All was going well in their new life at Gubari, when, in 1877, the Stainforth family was struck by a thunderbolt from out of the blue, and was devastated"

After an interview at the headquarters of the East Indian Railway Company, Henry was appointed District Storekeeper at Dinapore, Bihar State, with responsibility for administrating the flow of spares and equipment on the recently completed line through Patna to Benares. Their place of residence is given as Bitha, probably the European quarter of Dinapore, and their house would have been unostentatious in keeping with Henry's modest salary. Their expenses, however, at this point in their marriage, were not great and Matilda, who was used to living economically, was content. She was also looking forward to the birth of their first child, for no sooner had they arrived in India than she discovered that she was pregnant.

Their first-born son was born on the 29th June 1867, and was baptised William Rede Stainforth in the Anglican Church in Dinapore on the 10th November. Judging from other baptismal records in India, it was not uncommon to allow several months to pass between birth and baptism to ensure that the baby survived the dangerous period following birth. But baby William was a tough little chap who weathered the Turkish-bath atmosphere of the Monsoon, and gave every indication of growing to be a big man like his father.

The little family did not remain long at Dinapore, for within two years they were on the move again, this time to Lucknow, a city that Henry knew well and liked from his Army days. Henry was undoubtedly very efficient and good at his job, because his new post as Storekeeper at this important junction on the Oudh and Rohilkund Railway was a considerable step up with increased salary. Their house was bigger and better appointed in the part of the city that Captain Wyatt had described as 'a very handsome town', and which now boasted a good European club and a convivial social life in which Henry, an old Indian hand, felt very much at home. Matilda, too, having followed her father from one Army station to another, was no stranger to this exotic lifestyle, and was supremely happy. Perhaps the Lucknow period of their lives would go down as the happiest that either Henry or Matilda had ever known. Their second son was born on the 10th May 1869, and was baptised Richard Terrick (the third to bear those names) in the Anglican Church on the 13th July. A third boy, George Staunton, came into the world during the cool, dry weather on 2nd December 1870, and was baptised on the 4th March 1871. All three of her sons were healthy and well able to stand the climate, so Matilda called a halt to child-bearing and entered enthusiastically into Lucknow social life and the charitable work of the Anglican church community. Being a doctor's daughter, she had acquired nursing and first aid skills, which were much valued by European families during 'the rains' when childhood illnesses were at their worst, and on those occasions when the medical services were stretched to their limit during an epidemic. She was also young and attractive and had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances. The Stainforths entertained, and were entertained at dinner parties, attended soirees and receptions, and were generally much in demand on festive occasions. For the five years they spent in Lucknow life was very sweet for Henry and Matilda, and prospects for advancement were excellent.

Indeed, late in 1874 Henry received an offer of a job of such importance that he could not refuse. An opening had occurred in the Royal Egyptian Railways for a senior superintendent with proven administrative abilities, and a facility for languages. Henry was fluent in French and German, spoke Bengali and, after a crash course in Arabic, he was confident that he would be able to converse with junior staff in their native tongue. Henry's name had been put forward on a personal recommendation, and this major step-up in his career was not to be missed. So, sadly, because their time in Lucknow had been blissfully happy, the family packed up and travelled by train to Bombay to catch the steamer to Suez, and thence to Cairo.

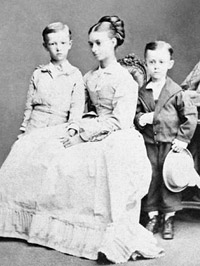

The only portrait photograph of Matilda in existence dates from this journey, and was taken in Bombay just before their departure for Egypt in 1875. It shows a pretty blonde girl in her early thirties in a plain white dress sitting between two of her boys, William and George, aged eight and four and a half respectively. There was obviously no time to buy the boys outfits for the voyage, because William is wearing his hot-weather clothes, while George proudly sports a sailor suit several sizes too big, with huge tucks in the sleeves and trousers, and his feet crammed into boots at least a size too small. Matilda sits relaxed, serene, deep in thought, her mind perhaps contemplating a future without financial worries.

*****

All was going well in their new life at Gubari, when, in 1877, the family was struck by a thunderbolt from out of the blue, and was devastated.

Matilda, as was her habit, was helping a friend nurse her little boy struck down by a high fever, and was appalled when pustules appeared on the child's face and hands. Smallpox! Matilda thought that she had been inoculated as a child against the dread disease, but in those early days of vaccination by 'the arm to arm' method she could not remember whether the vaccine had taken. Hurriedly, Henry and the three boys were vaccinated, and Matilda hoped for the best and isolated herself from her husband and sons.

After a fortnight, however, she herself developed the fatal fever, followed by the tell-tale pox pustules in profusion on her face and hands. In the isolation hospital the doctors pronounced that Matilda had developed the disease so badly that recovery was unlikely. And so it was. Matilda sank rapidly, and died without the comfort of her beloved husband and children around her. Henry would have been willing to take the risk of infection, but, for the sake of her three boys, she forbade it.

The manner of Matilda's passing obliterated almost every record of her life. She was cremated, and all her personal belongings, clothing, letters and books were removed and burnt. Her birth and marriage certificates, her record of baptism and confirmation, and her personal diaries went with the rest of her effects into the fires. Even Henry, overwhelmed with grief, omitted to register her death at the embassy in Cairo. It was as though she had never existed.

Not Found Wanting, pp. 316-18